Sometimes I Think About America

Gertrude Stein at Earth

April 19 – 21, 2024

For those of us wondering what sort of programming would populate the newly opened but vaguely publicized space, Earth on Orchard Street, an answer came in the form of a marathon reading session from Friday to Sunday evening, as a coterie of over a hundred artists, writers and downtown players worked their way through Gertrude Stein’s mammoth modernist tome, The Making of Americans. A revival of similar readings, dating back to the seventies, first took place at Paula Cooper and then at Triple Canopy. It was only the fourth public event at Earth, one that, like the Heavy Traffic launch that preceded it, further inaugurated the site as the physical manifestation of the nebulous community whose full-throated embrace of literary culture has reconfigured the scene on the Lower East Side, filling the space left by the galleries who have largely decamped to Tribeca (though emissaries from the galleries were well-represented among the list of readers).

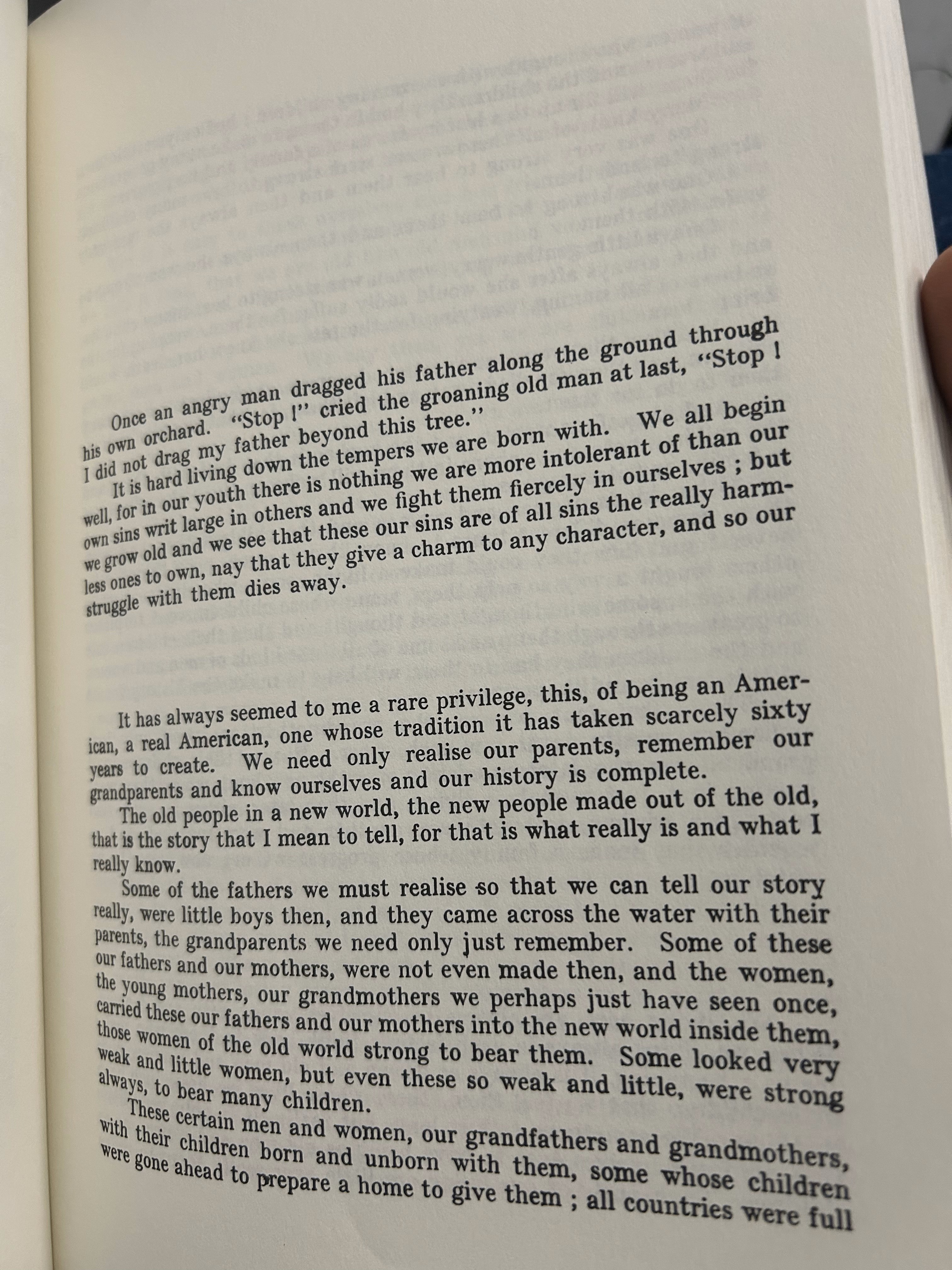

Organizers Walt John Pierce and Sam Frank kicked things off, giving themselves those juicy lines on page one which form not only the thesis of the ensuing nine hundred odd pages but seemingly the ethos of the event itself: “it has always seemed to me a rare privilege this, of being an American, a real American, one whose tradition it has taken scarcely sixty years to create.” Following them were a group that ranged from the aforementioned blue-chippers like Nate Lowman, Amy Sillman, Dan Colen, and Paula Cooper herself; to old guard literati Charles Bernstein, Vivian Gornick, and Lydia Davis (who read over Zoom); and those like Dasha Nekrasova, Sean Thor Conroe, and Natasha Stagg whose names are regularly trotted out whenever some new writer feels the need to share their take on Dimes Square. That such an event could draw, at once, socially revanchist, Counter-Reformational podcasters, and radical feminist critics speaks to the ambiguous appeal of Stein’s novel as simultaneously a formalist literary investigation and the embodiment of an Americanness that defines itself inwardly rather than outwardly — by its psychology and not its society. This was Stein’s decisive turn away from the social novels of the nineteenth century and their contemporary successors among realists such as Edith Wharton, her fellow expatriate. Whereas Wharton utilized the external social pressures of the age to shape her portraits of American society, Stein’s Cubist language games emphasized subjectivity, marking epochal change from within.

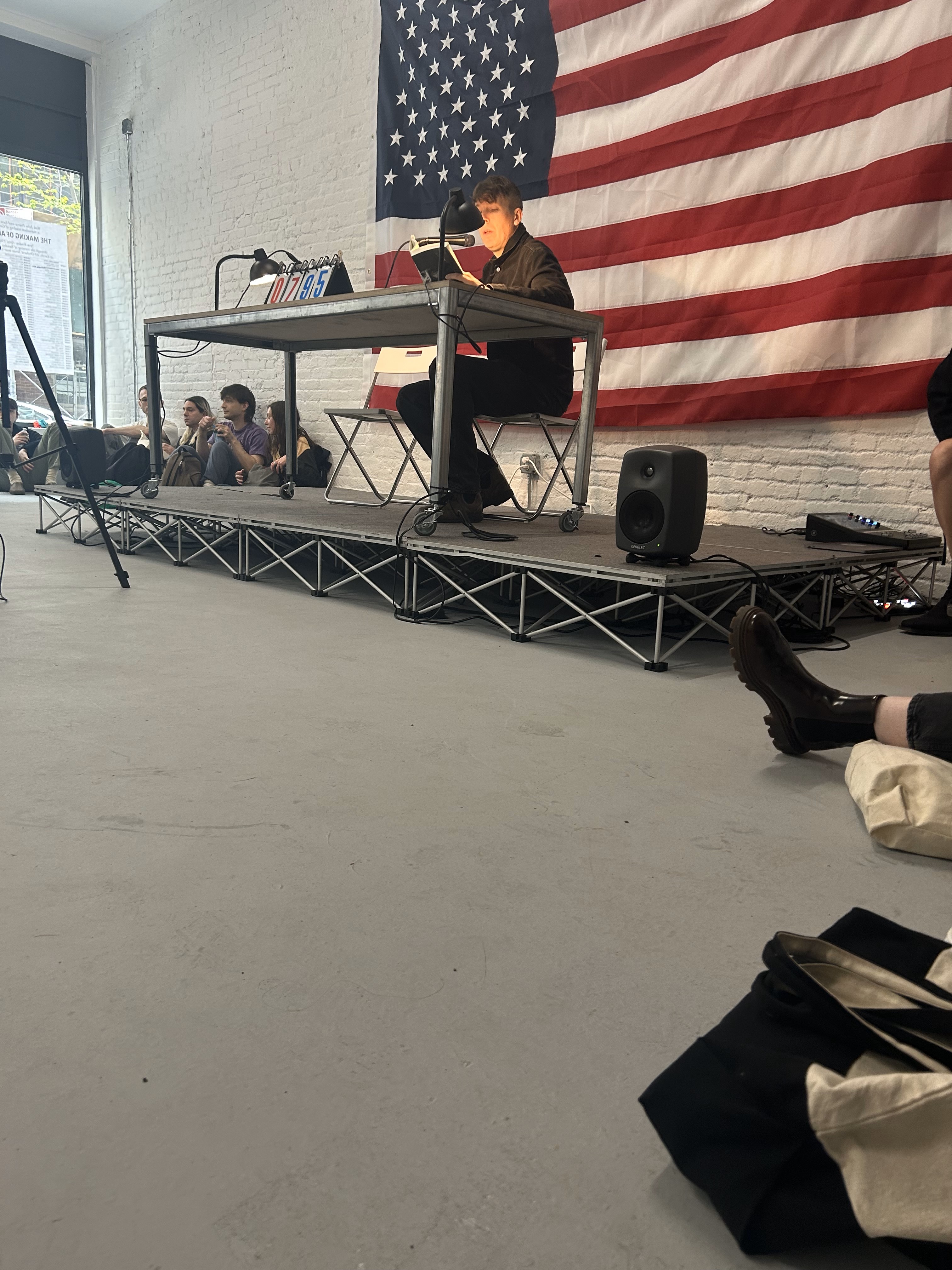

A century later, another turn is underway. As the industry plays catch-up with a decade’s worth of social movements demanding representational parity and political sensitivity, the downtown diarists are eager to assert that sometimes the personal is just personal. What Pierce refers to in Interview magazine as a “unifying event” is really a shared nostalgia for modernism, for a purity of form capable of temporarily sublimating the enormous American flag hung behind the stage from a fraught symbol into an impressionistic one, a gauzy remove that neither salutes nor desecrates it but points instead toward an aesthetic conception of America as an unencumbered, endless landscape, culturally impoverished but artistically open, the view Stein herself took to forcefully defending on her visits with literary society in Europe.

Inside Earth, the flag and accompanying folding chairs and tabletop microphones lent the proceedings the air of a local town council meeting, particularly when viewed from the grainy YouTube live stream that ran continuously over the three days. On the other side of the camera, spectators braced their backs against the scuffed white walls and darted onto the sparse cushions whenever one became available. Paperback copies declaring it “the first stunningly original disaster of modernism” were stacked in crates by the door or strewn about the floor; a dedicated few followed along religiously, but most were content to let the liturgical voices wash over them while they sketched in notebooks and glanced at their phones. One stalwart curator would not be deterred by this languid energy, hopscotching around the room to press the flesh wherever he spied one of the more illustrious participants waiting their turn in the wings.

Reading in calibrated, twenty-minute segments that neither dragged on nor whizzed by, the performers wrestled openly with the novel’s labyrinthian, stream-of-consciousness syntax, their often spirited openings giving way to torpor as the repeated phrases twisted back in on themselves. Rather than disrupting the event, these punctuated struggles served as its most perceptible content. It was only when the room erupted in laughter or fidgeted during a changeover that one was reminded of the presence of any real kind of audience. Literary marathons often perform modernist or proto-modernist works like Moby Dick or Swann’s Way as much for their non-narrative structure as for their conspicuous length. The form is not conducive to coherence, and even the most attentive listener would eventually succumb to unintelligibility. Better to drift in and out — Stein believed the essentially American form of motion was wandering — around the corner for lunch or to the curb for a cigarette, where the discussion is focused less on what is happening than on the fact that it is happening at all. As with any proper charity single, from “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” to “We Are the World,” the point is the names assembled, and the message is always unity.