Elsewhere or not at all

Lynn Hershman Leeson at Julia Stoschek Collection

April 11, 2024 – February 2, 2025

As I lay there gagging, choking on capital’s cock for my living, that is, for the waters of life that may redeem all the rents incurred by the crime of birth. That is, as I lay there, she appeared to me in a vision: “What would remain?” And “Would it be trivial to note that you’re just like everyone else?” And “Would it be trivial to note that Lynn Hershman Leeson saved my life?” Perhaps, and also untrue. But it’s hard to make sense of anything these days, and in that fugue her Electronic Diaries (1984–2019) strike me with the deadass clarity of the existential — not in the senses of Sartre, but the more prosaic German one of what are you going to do today, perhaps tomorrow, to make sure you survive. How to pass on those little blips of meaning, however infinitesimal in the face of time?

Cobbled together from found materials and confessional footage spanning around 30 years of the artist’s practice, the video essays combine theoretical reflections on art and technology with almost exhibitionistic accounts of her own life. Earlier episodes touch on her personal struggles with fears, traumas, and illness; low-key dysphoria regarding her own body and the discovery of a tumor in her brain. In one of the most harrowing passages, she recounts her friendship with Henry Wilhite, a black artist and dog trainer who suffered from a tumor not unlike hers and relays his plans for his remaining days in a series of candid headshots. Cue the survivor’s guilt.

As things progress, the focus shifts toward the rapports and friendships cultivated over the years. For example, with filmmaker Eleanor Coppola, who had her professional aspirations overshadowed by her husband’s and speaks openly of having them redeemed by her only daughter. Or with Elizabeth Blackburn, a Nobel-winning biologist known for her work on the genetics of aging, who cites Leeson’s film Conceiving Ada (1997) as a personal inspiration. Toward the end, Leeson returns to reflections on her own mortality, this time tempered by her faith in evolution, which led her to encode her entire archive into synthetic DNA — the longest lasting information medium known to humanity — and to develop a corresponding antibody. The possibility of both immortality and self-annihilation by design.

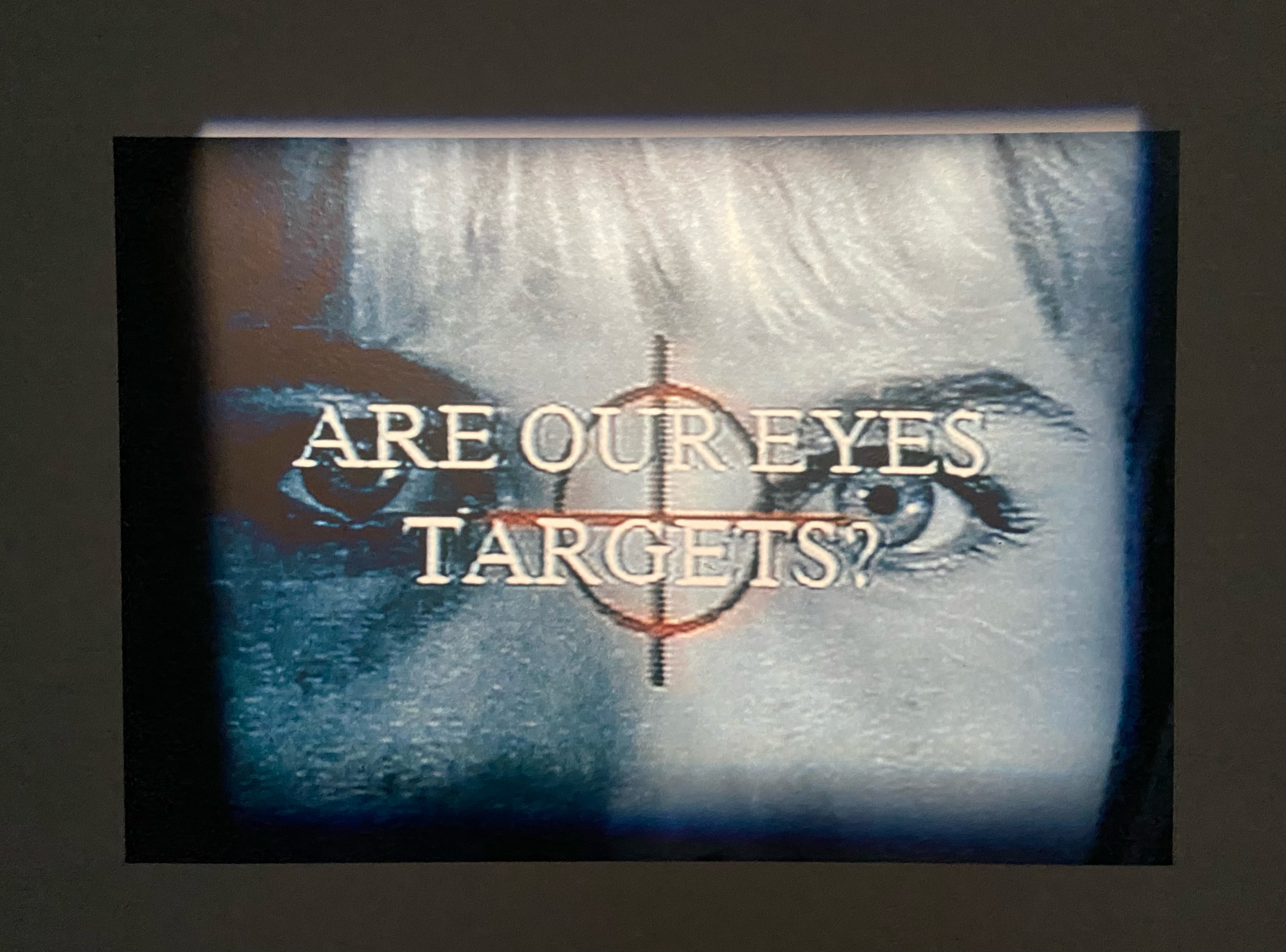

The rest of the show tries its best to summarize Leeson’s lifelong engagement with technology, which has been especially remarkable for its prescience. Seduction of a Cyborg (1994), for example, shows how the desire to escape one’s own body plays into the addictions of the terminally online. But even the most recent works, like Shadow Stalker (2018–21), about predictive policing, fall prey to Leeson’s love of lo-fi CGI, which ultimately leaves them feeling contrived and preternaturally dated — think Dara Birnbaum, Ericka Beckman — especially when compared to the intellectual candor and unfussy TV vernacular of the Electronic Diaries.

It’s a sweltering summer in Berlin, and the hormones are giving rabid. Still, my mind keeps circling back to Buchloh’s Exit Interview and his refreshingly old-fashioned insistence that any critique worthy of the name must inoculate itself against recuperation. Meanwhile Ms. Vishmidt chimes in from the ether to clarify that it is no longer enough to critique, but rather one must engage with the infrastructural “conditions necessary for the institution and its critique to exist, reproduce themselves, and posit themselves as an immanent horizon.” There’s little of that spirit to be found here — which isn’t entirely surprising given that the survey unfolds in the private foundation of a collector famous for declining to say much about her industrialist family’s Nazi past. Though by contrast, it becomes clear just how much of the show’s critical energies are invested in a discursive elsewhere.

To be fair, imposing criteria extrinsic to the work is a guaranteed shortcut to disappointment. And yet, the world just outside the door imposes itself on us all the same. As I type, Germany’s parliament is clamoring to pass a resolution that would have the equivalent of the FBI vet anyone applying to state grants for their commitment to “democratic values.” Meanwhile, a media frenzy of high-profile cancellations steadily chips away at artists’ and institutions’ willingness to address the here and now in anything but the most nebulously inoffensive terms. It doesn’t take much imagination to see where things are headed from here. In this light, the outcome of Leeson’s Electronic Diaries comes to feel symptomatic: We project into uncertain futures because, apart from our friends, reconciling oneself with the present is all but impossible.