Made in Heaven #1: A Roundtable on Perverts and Populists

In this conversation, we use Jeff Koons to look at what’s going on around us. Why Koons? One thing about Koons is that, like few others, he has come to embody the voice of reaction that the Reagan years ushered in, the backlash to the second-wave feminism of the 1970s and ’80s. He is thus often accused of being too affirmative of mass culture, identified as a symptom of the increasing cooptation. He is the moment when art loses its critical function.

We disagree with the expectation of art being critical in this very narrow way, an expectation that usually relies on turning art-making into an act of ethics of production and consumption, the hope that righting the wrong on the small scale may alleviate misgivings on the bigger scale. Thinking about Koons allows us to tackle the middle-class delight for austerity with a Baroque sensibility. So, what we want to talk about in the following is maybe not his greatest work, but one of his most important, Made in Heaven (1989–91).

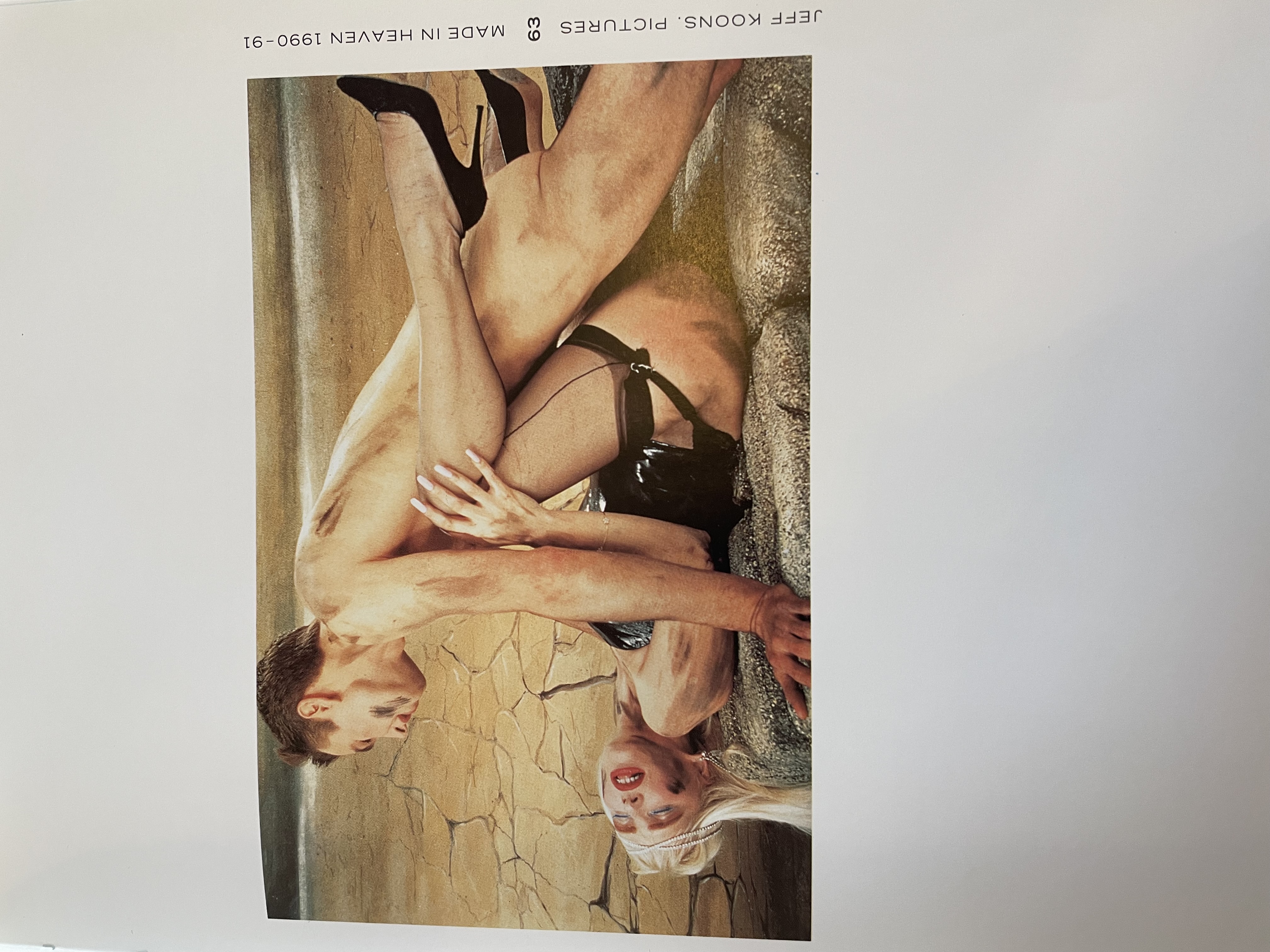

C: The works have this porosity. There’s one shot where Koons is behind Cicciolina, he’s coming over her asshole, and you can see little blemishes on her ass. There’s a sort of realism when I think intuitively I would have expected them to be slicker, but that's because it’s the ’90s.

A: In this YouTube lecture, he goes on and on about the blemishes on her ass.

C: So he’s into that, okay.

A: They’re quite composed, often following historical references like Monet.

D: Right. Or Jeff, in the position of Adam. They have these classical gestures, but then they are also using these pornographic tropes like the cum shot.

C: Yeah, pornographic tropes, also in the backdrop. Now we were kind of talking about petty bourgeois aesthetics. I’m looking at this ornate set of horrendous Champagne glasses, which could both fit in any middle-class home or pornographic set.

A: But why are there six glasses? You know what I mean? It doesn’t make sense that there are six glasses. Some images just show her, some depict both of them, some just show body parts. In some, you can see that it’s shot in the studio, and some have these quite cinematic backgrounds. Like hell. Or there’s one I really like, which is called Dirty Jeff on Top, in which they are supposed to be in the desert and he is dirty, but it’s also just very artificial.

D: You can almost see the marks of muddy hands just decorating him.

C: I don’t know if I am projecting now that I’m paying so much attention, but I was thinking that you can see the discrepancy between her having been a porn star, having been someone working actively for the gaze of a camera very much within the field of the pornographic, and Koons himself. He’s doing a fair enough job, I suppose, but in the full-body shots, he really takes me out. For example, in Fingers Between Legs, it’s almost like the vampire effect in advertising: He’s taking me out of the sex.

A: He’s also not aroused in this picture. And the ones where he’s aroused, you can’t see his face. So yeah, I agree. How would you describe the voyeurism in these pictures?

C: It’s almost like slapstick. I mean, with a little fantasy as a straight person who has sex with people with penises, I still feel aroused by some of them, but not by those where I can see Koon’s face. It disturbs basic voyeurism.

A: Looking at these images, I was thinking of how amateur porn emerges in the 1980s as a relatively new phenomenon. And then I was looking at those images and wondering, Is this supposed to represent a kind of American middle-class vernacular?

C: No, he’s looking at Italian porn. He’s looking at the porn that Ilona is making.

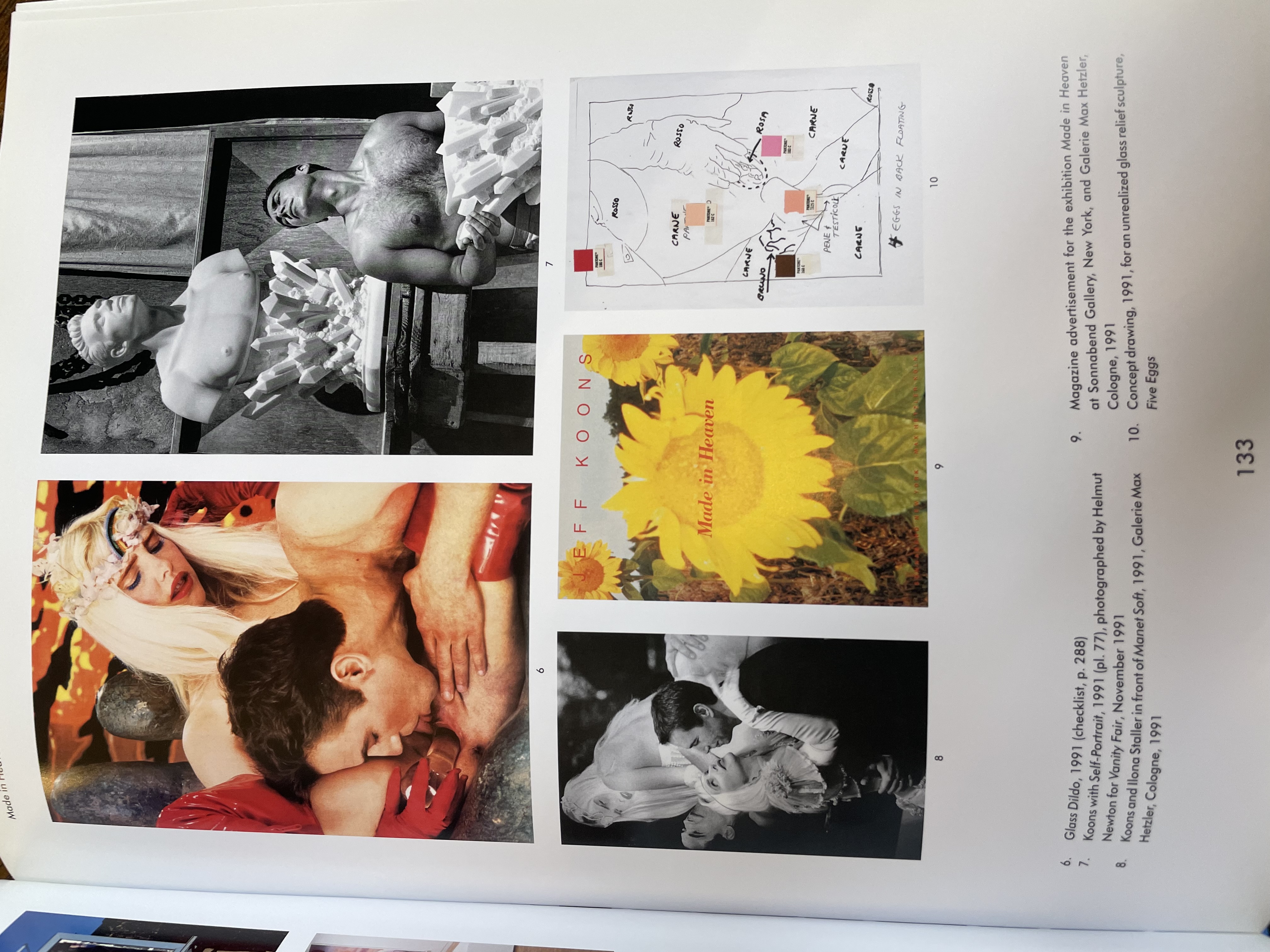

A: I watched the BBC documentary where he talks about wanting to make a movie, and this is the billboard for the movie. Like the iconography he relies on is that of a Marlon Brando movie. So yeah, it is advertisement, but I think it’s actually movie ads. Maybe that’s a good point to transition into the Pamela Lee essay, “Love and Basketball.” She is a student of the October journal clique and asks the question of critique. And she says, well, Made in Heaven is not only about increasing the co-option of art but also about the conflicted fortunes of our criticism as well. It both makes criticism very important but also brings it to its limits.

B: Well, the problem with Koons is that the point of these works is to show and enlarge something that a certain subset of people finds shameful. And then to confront it in this larger-than-life scale, one realizes that shame is silly and then comes into their own power and owns it. And this is a neutral thing, you know, like that’s not always a good thing. It’s not always a bad thing. But to use two silly examples: You have like Black Lives Matter, you have a shamed body who overcomes its shame and goes into empowerment, hence the uprising. So, that’s the good object. And then, on the other hand, you have incels, people who are ashamed of not being able to have sex and then coming together online to own this and then start shooting people. So, what’s the difference between the two? Well, the difference is criticality and so on.

C: I love how you made it very clear what he wants. At some point, he says, “I want to show people how to have impact,” and then it occurred to me that for Pam Lee the obscene thing really is that he states that he wants people to affirm their desires. The obscene thing to her must be that he’s not telling us that we want the wrong thing. So that is where the criticality is missing. So, he’s saying, “Okay, I want them to freely look at images of sex or maybe have sex with each other.”

A: Because Pam Lee and her peers think that desire is a bad thing that must be questioned and that we must distance ourselves from. Desire is capitalism, desire is sin. So, this tradition of criticism argues for a type of art that questions our desire. Like the big antipode of Koons in the ’80s are of course the Pictures artists who show us that what we want is patriarchy.

B: I think Jamison Webster says that all desire is a desire to transgress one’s own narcissism. Koons is not critical of sex or desire. I think he’s critical of shame, which is another form of narcissism. I think shame is quite useless because it doesn’t actually get people to change. Because they enjoy it too much. I don’t know if any of you are close friends with addicts, but when you shame an addict, it doesn’t work because they love it. They love it too much and it’s part of the cycle.

D: This makes me think of these 12-step programs that make you hate yourself less: “You know everything about you is perfect.”

C: Postmodern addiction gone awry. This is why I thought of Tom Cruise in Magnolia. A person with a smile and the Scientology underbelly. There’s something about these impenetrable phrases.

A: Made in Heaven started off as images of desire in which he commissioned Ilona Staller. Later he said that “she was the readymade and I just got in.” So, she was the famous pornstar that he hired to do this, and during the shoot, they fell in love and got engaged. And then in a later iteration of the project, I think after it was first shown, they got married, and then he added a picture of them standing in his studio with a massive wooden cross behind them while he holds her just below her exposed breasts. It started off as a project on desire and turned into a project on family values.

D: A true love story.

A: Imagining a suburban middle-class family love story. He wants to heal the family.

C: This is the restorative dimension, with a reactionary potential. I am not proposing that Jeff is on par with the Reaganite right. But I think I was thinking about restorative as in sort of recuperating wholeness. Because I was having such a hard time understanding what he really wants us to do, other than having sex. And I’m not satisfied with the idea that he’s just showing us sex in order to normalize it. It’s more about restoring something broken, which would sit well with his Protestantism.

A: So what is broken for him is both the family and the genre of the female nude? This is him working through 19th-century neoclassical painting. Of course, these are not just photographs, they are what he calls “photo-paintings,” basically ink on canvas. I think this ambition to return to painting, a return to genre, is part of his ambition to rebuild the institutions of the middle class. And just before Made in Heaven, he made these stainless-steel trains. They are these small steel train models that run on whiskey. And he talks about these trains and the whiskey as a blue-collar imaginary. So, first comes the working class and then the middle class.

D: I think it’s specifically not middle class because he aspires to a classless society. Everyone is “blue-blooded.”

C: I still feel like it’s not so clear what he wants. I think there’s two things: He must have felt a distaste for the styles he’s opposing, like the criticality with a hammer. And then there’s this other thing, this aspirational restoration, which I don’t think necessarily goes hand in hand with the other ambition. Because if you just want to destroy the specific formal criticism of a former generation, then you don’t have to go full-on Gesamtkunstwerk.

B: Both of you actually used interesting words. You said repair. Like, are these reparative or are these aspirational? And I think that’s the unresolved tensions in the work. So on the one hand the work is saying, “Oh, here is an ideal love and family that you’ll never have and you want this and you’re just never gonna get this. And I’m representing an impossibility in the way that religious art did.” On the other hand, it is repairing one of the foundational myths of Western contemporary life: He contests the complex that all families are failures, all marriages are failures, by showing that you can actually have a perfect loving family completely devoid of shame. It oscillates between the two.

C: Combined with the story that Jeff and Cicciola met on set while fucking and cumming cements this point of sincerity. Like, he’s meeting the love of his life, then goes on to marry her, gets taken pictures of by Helmut Newton, has a baby boy, and reaches the apex by having a custody battle.

D: His stated goal was to make a movie, but actually what happened instead was that he made a family and he made it like a billboard. A horror movie. Something about that feels really fertile. Because I think in a way he’s trying to reimagine an original sinful act as shameless and therefore pure.

B: I’m not quite sure if what I’m looking at is love or desire. It makes me think about that quote where he says that she’s a readymade, which means that he is also a readymade, right?

A: She’s the Hoover.

B: And he’s not? How is he not also a Hoover?

A: I think he sees himself to be the Warhol, the one who puts the Hoover in the museum.

C: Pamela Lee says the following about purity: “Purity is not about a sin-free record or a spotless mind but it is, paradoxically, an amoral condition.” Amoral for her is the lack of a concrete critical viewpoint. If we think of Martha Rosler as an enemy of Koons, a person insisting on something that one could call the anti-corporeal or anti-figurative as a critical stance, then Koons’s purity is also going against her. This is the amoral purity of the nude that is going against the bourgeois insistence on critical art while also insisting on a certain iconoclasm, not showing certain things because they represent a threat to criticality (read: decency, taste).

A: She’s quite specific about what he is doing wrong: “The peculiar heartlessness of the images and the act as their blithe indifference to such contemporary events or critical phenomena channeled a different kind of message.” The critical phenomena here are feminism and the AIDS crisis. I think we should speak about this because intuitively it makes so much sense: Oh yeah, showing this type of work during the AIDS crisis seems incredibly cynical, amorality becoming immorality. How dare you depict sex as people are dying from sexual encounters. Straight people exhibit their sexual privilege as gay men are dying from sex. That’s, I think, the heartlessness she sees in this work. And as the sexuality of gay men is increasingly policed, the other side is happily indulging in their own fantasy.

B: This is interesting because during the AIDS crisis there was a really intense debate in the queer community about shaming sex and specifically shaming sperm. And there was a lot of effort to move gay sex out of shame and to say no, we can still have this and we can still be proud of this. And so when I look at these works, I see a lot of sperm, and sperm is the same if it’s gay or straight, it’s the same. It’s just as dangerous.

C: It stands out to me that these images are not abject.

B: They’re actually not abject, which is important.

C: I do like that you point out sperm being a focal point because I was already on my way to think that this work is almost asexual. But then maybe there’s something about the messiness of sperm. The sperm definitely helps me to move it a little bit away from the slickness of traditional representations of sex.

A: We talked about the family earlier. Is this supposed to be a family album? Like your children and grandchildren are supposed to look at it decades later and say, “And this is where auntie and uncle Koons fell in love.”

D: That’s why his smile is so amazing, and it’s kind of the same everywhere. It’s just like someone behind the camera is saying cheese. It’s impenetrable, unreadable, but he seems satisfied. He seems vaguely happy, like you would look in a photo album.

A: If you watch videos of him on YouTube, he is like Tom Cruise, only much better at being this American middle-class normie who shows up at your door and sells you a vacuum cleaner. That’s what he wants to be: The salesman who comes to your house and this large smile comes up, looking straight into your eyes: “Yeah, you should buy this, you need it.”

C: And why is that? If we stay with Tom Cruise for a minute and Magnolia, like when he’s giving these aggressive sales pitches to men in this proto-incel culture situation, teaching them to be more. Koons does not want to do that because he does not want to discomfort us. Is it that he is more sincere? Does he really believe it all?

B: Yeah, he definitely believes in it, all right. But you can feel that in the works. I have salvation, just believe in me.

A: What brings Koons and Cruise together is that they want to give middle-class suburbia what they want, in contrast to their opponents, who want to say what you want is wrong. Let’s clean up America like it was a dirty carpet in the living room.

C: The 2019 news item was that Jeff Koons is retiring from art and close friends say they’re worried because he’s found spirituality. Has he ever broken in public? Maybe he doesn’t break.

A: It’s hard to look at Made in Heaven and not think of the really, really, really messy divorce and what many commentators called the “traumatic custody battles.” So, in the mid-’90s, he’s breaking and doesn’t do any shows for seven years, until his New York return with “Celebration.” Like, when you watch videos of him and Cicciola, you can tell that he wants to turn her into his housewife. And famously, the thing split apart because she didn’t want to stop making porn.

C: That’s too good to be true.

D: He wants to give the people what they want, right? He’s clearly interested in communicating with some sort of universality, but I think there’s actually a real difference between what he says his desire is for the Made in Heaven series is — this kind of self-help language — and what kind of needs he is actually meeting.

C: That’s a friction point I was also grappling with. A populism, or the pretension of some kind of populism, meets a blasé spirit of the bourgeoisie looking down on the little people and their desires.

B: I have a really simple question: Why is depicting sex bad or wrong or something we’re not supposed to do? Why was this work sequestered away in the hidden secret room at the Whitney retrospective all these years ago?

C: I tried to post Ilona’s asshole yesterday and it got immediately flagged and banned. I don't even want to bore anyone with Instagram policies for nudity, but that’s just it. It’s kind of amazing what we’re doing there, like the most used social-media application and there’s nothing you can do. No asshole, no fucking, no penis.

A: Is there something in Koons we should hold on to?

B: I think there’s something kind of optimistic about his utopia and the depiction of an ideal perfection, even if we know it’s totally constructed.

C: The first time I saw the Gazing Balls, I thought those are what we deserve as an art world and that that’s not a good thing, but also not a bad thing. And personally, I’m interested mostly in that initial branching off into populism as opposed to a closed-circuited inside conversation that channels the middle-class criticality of humans as defective.

D: I would call Jeff Koons a shameless artist, and I think there is a lot to aspire to in being a shameless artist.