Everybody is depending on you: A roundtable on becoming an artist

In this roundtable, we discuss the training of artists. We use Jeff Koons’s 2020 MasterClass™ as a reference point to consider what a study guide for artists looks like, what skills making art requires, and how assignments work. We talk about competing methods and ambitions, about artistic processes and products, and where this expenditure of human capacity might take us.

C: Let’s start at the beginning. How do you learn to be an artist? I watched the master class, and just before I happened to go to the Joan Jonas show at MoMA. There’s the Art Education syllabus room, where you can look at a syllabus she composed for a class in Venice, and it starts with the words, “You cannot learn to become an artist.” It’s a very basic romantic idea: Art is something inherent to a person, a special person. I think Koons offers us a very different model of art.

D: He takes on a paternal role in the master class: “You can do it, too. It’s all in you. Just enjoy yourself.” He has this motivational-speaker aspect to the way he’s talking to you. He’ll say something, and it’ll be repeated in writing on the screen to burn it into your mind.

B: “Remove judgment.” “Your self is not going to fail you.”

C: Toward the end, I think there’s the scene where he talks about how his dad would exhibit his art when he was a boy. There is something about repeating that affirmative childhood experience. He seems to be narrating this: “Yeah, you can do it. You can be an artist.”

D: It just underscored how important fostering a child’s creativity is. And giving them an opportunity. Showing them respect for their ideas at a young age.

C: But he also has quite specific techniques he thinks can help someone become an artist. It’s different from Beuys’s “Everybody is an artist.” Koons is not saying everybody is an artist but that everybody can become one. There’s that democratic Utopianism inscribed, but it entails a very specific set of things that you might learn.

D: I kind of agreed with most of what he’s saying. I was a little suspicious of how positive he was.

B: Because it’s psycho.

D: It is psycho. What was really effective in that video though is that he’s pointing at everybody having the potential. It’s ultimately this selfish idea, you need to just believe in yourself and follow your own interests. Because if you follow your own interests, you will go somewhere. If you don’t follow your interests, you won’t go anywhere.

A: This is the part where I found myself agreeing with him the most. But I find myself skeptical of these pleases on his part: “Please have a voice with your art. Everybody is depending on you.” He can’t stand negativity. Whereas I think a more interesting pedagogical approach is to deal with negativity in a productive way. But he shunts it out completely.

D: Isn’t there a whole passage toward the end where he talks about getting critiqued?

A: He says that what’s exciting about showing your art to other people is that you get to learn what other people are interested in and what they’re responding to. And sure, people are gonna say “bad things about your art,” but he says “in the long run, I know my intentions are good,” or “you’re the only person that knows if anything has any meaning, and if something can be made better.” This withdrawal leaves things a bit meaningless for me.

C: I agree, there is a tension between, on the one hand, this idea that the resource for making art is your individuality. You’re supposed to create this personal iconography that’s based on your interests. That’s you, you, you. But then, on the other hand, the whole process is about creating symbols that speak to other people. And at that point I think you can very much talk about criticism: which forms are more effective, which forms are less effective.

B: But then it’s about finding in the self the best thing to present respectfully, to create this relationship with the other person. This is why I can’t get over seeing him like a little child. It was so interesting to me that you said he acted like a father figure, because to me all I can see is a 3-year-old. “Look, I’m making. I’m making. Love me. Look at me, love me.” So it’s interesting to have a discourse that’s seemingly about the self, but really is just in the service of getting in touch with other people. And it’s more interesting than just wanting to be loved, because he doesn’t really want to be loved back. He wants to give.

A: In order to be an effective teacher, do you need to get onto the level of the people that you’re teaching?

C: I wouldn’t actually agree with that. But in his case, that’s the technique. He infantilizes himself to speak to us, his children.

B: He’s always already there. That’s what it looks like to me.

D: I don’t really see him as being infantilized. I just see the salesman in him. He seems incredibly friendly and relaxed. It’s the same tension in his work. You look at the work, you look at the pink panther. And he’s hugging the woman, and it’s cartoony, but it’s so dark, all his work is so dark.

I kept thinking, actually, that Koons and David Lynch are from a similar generation. And they deal with the same American, white-picket-fence iconography, with bugs on the inside. So he’s playing Mr. Rogers, but then there’s a picture of him, you know, having sex with Cicciolina.

C: I just found the notes I took while watching. “Disjuncture: kindergarten speech for expressing perversions.” That was referring to the pink panther work. He talks about it with a soft voice. It’s like “Ah, you hold me, you’re embracing me.” And at the same time the work itself is so fetishistic. Even the Celebration works are so ambiguous about anality, orality, all these things, but then he talks about them like he is standing in front of a group of children.

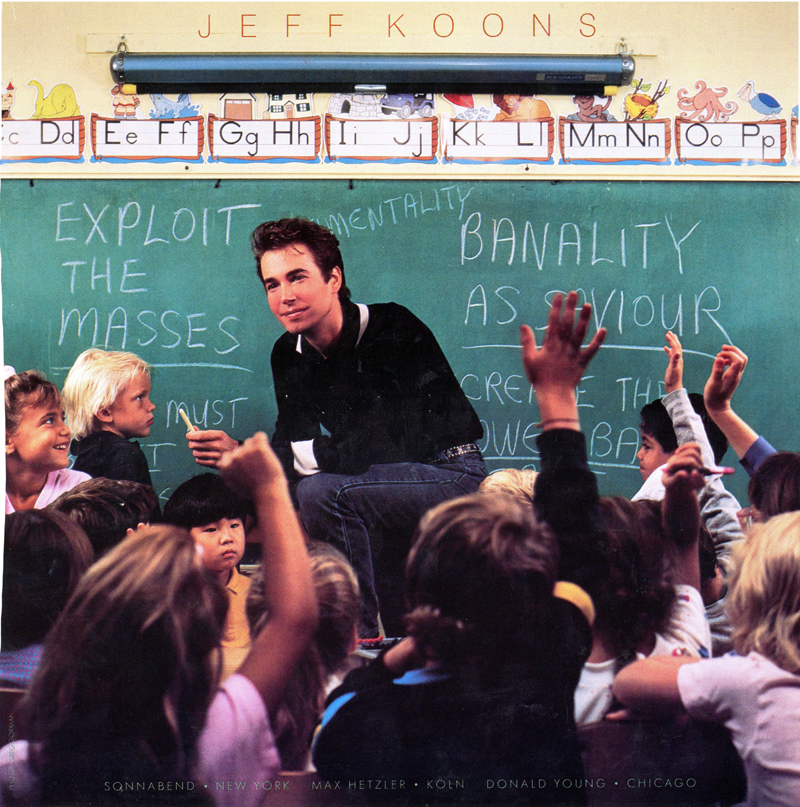

D: Remember that photograph of him talking to a class of children from the ’80s?

A: It’s part of the suite of ads that he does for Banality where he does a few different ads for a few different art magazines. And so he decided that the one for Artforum would be him teaching a class of children about the importance of banality. It’s a photograph of him in front of all of these children, the blackboard in the background.

C: I think on one side of the board it says “banality,” on the other side it says “exploit the masses,” which he doesn’t comment on in the master class.

A: This is the Koons model, he seems to apply it to himself and his artwork equally, which is, take something imperfect, and then reproduce it. And because you can reproduce something, you can make a perfect reproduction. This is his only access to perfection. Then you can say, “This is a perfect reproduction.” But you can never just take something and say, “This is perfect.”

C: But according to him art is the one realm where perfection is possible. And I think that’s why he’s a proper classicist. I think that’s so important: Art is this one thing that allows us to lift “man” up from the natural into the moral state. And that’s why the surfaces must be perfect. Because if that isn’t perfect, then we can’t even strive for it in our imperfection.

B: I was frequently thinking of Schiller when he was talking, because it is that same desperation, I have acne skin pockmarks, and now I’m going to talk about perfection as this thing that will keep me safe. So I do find it anxious. I can only understand this whole positivity as a supercharged defense, which, however, doesn’t undo the positivity. I just think a lot of the energy here comes from an underlying anxiety.

A: Have you read The Artist’s Way? It’s this self help book from the ’90s that teaches you how to unlock your creativity. It is extremely good. It's like the Bible for learning how to be creative.

B: It’s extremely annoying also.

A: It’s about dealing with fear more directly. You don’t ignore the fear. You write down a list of people you’re envious of, or you draw a circle and put people’s names in it who you think will help you be creative, and you put people’s names outside of it who you think would get in your way. It’s all about reframing or dealing with your negative thoughts or your defenses and understanding them on the path to becoming creative.

C: Obviously everyone has fears, and certain trigger points. But I think Koon’s ambition is to understand your own inhibitions, and then create artworks that allow people to realize their inhibitions. Made in Heaven or Banality or Celebration are very much about that. They’re all in different ways playing with that idea. In the Celebration series, you get to feel so many things in looking at these works even though they’re just these blown up balloons.

B: It is a very successful reorganization of the negative feelings that take place there. They’re now being utilized, they’re now being pulled into the positive realm where they can be productive for your work.

A: But my skepticism of Koon’s is not that he’s unable to do that, but that he doesn’t tell you how. His mode is Oh, someone said something bad about you, just wake up the next day and be happy.

D: He just keeps smiling. People are throwing mud at him, and he’s just like, “Everything’s great. Just believe in yourself.” There’s no vulnerability whatsoever. When I think about the pink panther, that’s one of the only times I kind of see him, like the real him, somewhere, but most of the time, it’s that chrome polish

B: That’s so true.

D: You know, I’ve always seen those sculptures, and polish, like this is like the highest level of fabrication. But I didn’t know about the CAT scans. And I didn’t realize that the actual structural integrity of those steel sculptures mimics the actual structure of the balloon, and that he mapped the exterior as well as the interior, and created a 3D model that has full integrity volumetrically. And now I was just like, Wow, you are so psychotic. That’s one of the most important points in his master class, when he only talks about Bob Hope (1986), and he’s like, “I lifted up the figurine and they didn’t put on the felt. I really wanted the person who put the sculpture on the pedestal to know that it had full integrity as an object.” That was the strongest lesson for me. You don’t just make something that’s optically pleasing. Even the parts you don’t see are important.

B: Even the parts that we don’t see are important, however, they are important in having to be exactly like the original.

D: He just keeps smiling. People are throwing mud at him, and he’s just like, “Everything’s great. Just believe in yourself.” There’s no vulnerability whatsoever. When I think about the pink panther, that’s one of the only times I kind of see him, like the real him, somewhere, but most of the time, it’s that chrome polish

B: That’s so true.

D: You know, I’ve always seen those sculptures, and polish, like this is like the highest level of fabrication. But I didn’t know about the CAT scans. And I didn’t realize that the actual structural integrity of those steel sculptures mimics the actual structure of the balloon, and that he mapped the exterior as well as the interior, and created a 3D model that has full integrity volumetrically. And now I was just like, Wow, you are so psychotic. That’s one of the most important points in his master class, when he only talks about Bob Hope (1986), and he’s like, “I lifted up the figurine and they didn’t put on the felt. I really wanted the person who put the sculpture on the pedestal to know that it had full integrity as an object.” That was the strongest lesson for me. You don’t just make something that’s optically pleasing. Even the parts you don’t see are important.

B: Even the parts that we don’t see are important, however, they are important in having to be exactly like the original.

D: I had a teacher in school, and she said something like “What does God see?” But she just meant that as you have to consider the parts that the viewer can’t see. A lot of his work possesses an aura, where you walk in the room you’re like, That thing is vibrating in space as a physical object. And I think that’s something he’s fully aware of. There’s something just in the basic structure of the object that compels you and supports the idea fully.

C: His provocation is that he is an artist that’s working in the legacy of classicism and not romanticism. He holds on to the classical categories of art education, including his favoring of invention, proportion, composition over expression and coloring. The master class is divided, not really well divided, but in segments. There’s a segment on scale. There’s a segment on form. But the center really is composition.

A: He talks about making this Venus of Willendorf sculpture, he makes it out of a balloon, and he works with the balloon artist, and he ends up making hundreds and hundreds of these little models that he then chooses from to do the final CAT scans, and this is the only moment where you see him editing, or there is an element of self-critique where he’s deciding what is good and what is not. Which is in contrast to his “manifesto in the spirit of the avant-garde,” where he says criticality is gone.

B: “Suspend judgment.”

A: This is Koons at his most autistic. The whole master class is full of these “contradictions.” No criticality on the one hand, and yet obviously, he’s always striving toward this idea of perfection.

D: I think he’s trying to convey that you need to find freedom. It’s about escaping these constraints that are constantly weighing on you, casting doubt in your life.

A: It is an attitude that is not common in the art world, but I see this in fitness all the time. My coach says things like, “If you’re worried about something being too expensive, just go out and make more money.” It’s a very literal approach.

C: It’s not just attitude, there are a lot of specific skills that he conveys that go beyond “Just believe in yourself.” He teaches you what to do with art history the same way he teaches you how to deal with the objects that you’re surrounded by. His marble Pink Ballerina sculpture, for instance, is in competition with Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne. He makes it clear that you must know art history to be able to communicate through art. In classical education, you learn from ancient sculptures to select from nature. You start by just copying over and over again the Belvedere Torso in order to understand where to cut nature off. And what he does in some way is to do the same thing with the modern world.

B: But the thing is he literally doesn’t say all these things. He just performs them, and you are extrapolating them. We can extrapolate them. But he’s just not doing the thing that you would actually think that one you do in a master class. To me it looks, and I don’t think that’s a bad thing, that the editor retroactively is trying to put things in order to make it look a little bit more didactic.

D: I really like that he shows those binders. That’s the most fascinating thing to see in the studio. He shows these binders of postcards and clippings.

A: This is his one moment of practical advice, which is get a binder and fill it with what interests you.

C: His idea of creating a personal iconography.

D: I’ve never thought of it in those terms, but that is exactly what every artist has to do. You need to create a set of symbols that you can arrange and play around with. You’ve probably had like three or four things for your entire life that you’re always going back to. And the more you indulge your own creativity, the more you realize that these things repeat. What was really strong is that he asked the viewer to think about what are the symbols in your life that have stayed with you. That you continue to come back to, and that can help yourself to define your own creativity.

C: It was the same thing when he talked about color and materials. He became very specific. Wood communicates this, porcelain communicates warmth. Forged steel communicates perfection and coldness. Red symbolizes this, and blue that. He creates a kind of vocabulary for this iconography. I don’t think you need to agree with the specific terms, but he gives you an example of what creating a personal iconography entails, which is, creating this syntax. And in his case I think it’s deriving from Renaissance ideas of materiality and color schemes. What is the symbolism of red? And then he tells you.

A: In these moments I can see how good he is at talking to collectors. He’s such a pro at explaining why he does what he does and what it means, and fitting it into this really neat schema. But he’s wrong. His whole thing about porcelain and sexuality in the bathroom.

D: That was pretty funny. He says people have their first interactions with themselves in the bath.

A: His mind isn’t dark enough to allow himself to say that this is about learning how to take a shit. He can’t do it. So it has to be this slightly removed anecdote. Is he masturbating in the bathtub? Is he looking at himself in the mirror?

C: The works are doing that.

D: They’re showing you a picture of this woman in this bathtub. So you’re like, okay, I know exactly. He’s talking about Duchamp’s urinal. It’s shit, sex, piss, cum, whatever. But he’s doing it with this Mr. Rogers presentation.

C: During the last Koons round table he was constantly being compared to Tom Cruise. This time it’s Mr. Rogers. Maybe we have a new comparative male role model every time.

D: I was really glad he talked about the train set piece. That’s one of my favorite pieces of his. And I really like that he specifically chose stainless steel, not silver.

B: What I think is interesting is that there’s often, like in an Isabel Graw line of thought, the idea that you imbue the object with magic and fullness by the hand of the artist. But here it’s not the hand of the artist. Here, it’s the thought of the artist, the decision-making of the artist, the order of things, with what you start and where you take it, and then the absolute commitment, and taking it all the way to the end. That’s a very compelling counter argument to the more literal idea of the touch.

D: I don’t think they’re exclusive. All that work is incredibly handmade. He has all the workers. He’s pushing all these workers. He’s still looking at it and saying, this has to go further. His assistants are just extensions of his body.

B: In the reception of art, there’s a lot of people that believe that the magic of the art work comes through the literal bodily touch of the artist. He’s finding a very convincing alternative to that. He’s truly managing to activate objects by something else. And in the way we’re always talking about some kind of animism. We’re talking about how do you make an object holy. How do you get the energy in there.

C: I want to talk about the problem of composition. Right now, if you go into most exhibitions, there’s two alternatives. There’s the romantic one, where the composition is the emanation of an artist’s personal intuition, where you get some post expressionist kind of stuff (the obsession with the artist’s hand). Or you get the Ghislaine Leung conceptualism, where it’s derived from a structure, like an institution. That second trend is closer to Frank Stella and his “deductive structure.” Composition is entirely determined by an external reference point. Koons way of dealing with composition doesn’t fit into either of these camps. It’s neither simply his intuition, him saying, “Oh, I’m the artist, and I make the rules.” Nor is it simply determined. His compositional principle seems to be about maximum effect on the viewer.

B: His work is completely in the service of communication. This type of perfection is done in the service of creating this relationship to the viewer. That’s why I’ve been wanting to talk about religion this entire time. It relates. We’re gonna make the perfect object, perfect painting, whatever, in order to imbue the object with a sheen of godliness, which will then do the utmost to communicate to the recruitable Christian.

D: I kept thinking about his insane perfectionism. Equilibrium is a perfect diagram reaching Nirvana. How did he get a basketball to float in the middle of a tank? They’re so tranquil. It’s not encased. It’s actually just suspended. Reaching that sublime state is super meditative. His best work reaches this higher meditative state.

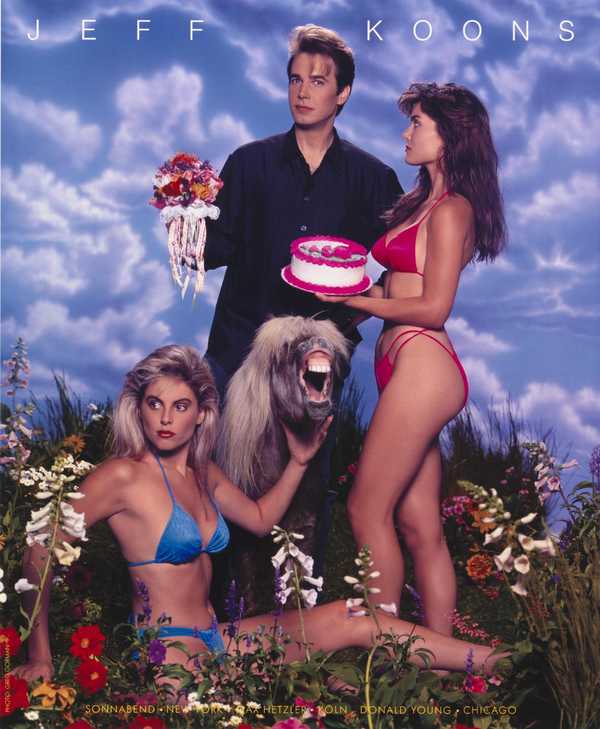

A: Jeff casts himself as Jesus in the advertisements in the ad for Art in America. It’s him with his disciples, which are two seals. Or there’s this “temptation,” where he’s on a donkey, and there are these “young women,” as he calls them, in bikinis trying to feed him cake. He’s come to save us from ourselves.

D: That’s the thing that he doesn’t really address in the master class. He talks about how he makes these things but then he never actually talks about himself, how he has created himself as the overarching project. There’s an elephant in the room. Which is that he is an insane guy. And actually me interacting with this video is me interacting with that idea that you’ve constructed. Which is the most alienating aspect of him.

A: The only time we see him crack is when he’s making a balloon dog as an example onscreen. It’s squeaking a lot, and he’s focusing on it very intensely. But the balloon dog ends up a little bit lopsided. The back legs are too short in relation to the front legs, and you can see he’s anxious to hide his mistake from the viewer. And then at the very end of the master class, he picks it up and says to someone offscreen, “You didn’t like that one, did you?” Finally we see this moment of him as a human who may fail. He’s talking about perfectionism but can’t make a perfect balloon dog. Is he, as an object, in a different class of things than the perfect objects that he’s making? Or, are the perfect objects that he’s making becoming part of him, allowing him to become a more perfect object? Or is he just a perfect object already, like the things he makes like?

C: There’s very little transformation in his story of how he came to make art. He only hints at it when he talks about the stainless-steel train: He suddenly moved away from the readymade and the obsession with preservation to the actual manipulation and fabrication of objects. That’s a problem in his master class: Wouldn’t it be important for us as students to have him disclose his struggles?

A: The only struggle is this Kiepenkerl statue where the casting turned out wrong and he had to fix the statue and build it again. This is the most traumatic thing for him. What other people usually do is exhibit the failure, but Jeff exhibits how he fixed it. The whole situation for me is like his Gazing Ball series: You just get this blue surface and retain it.

D: Yeah, it’s a strange story that made me immediately think about Duchamp’s Large Glass, which is really the opposite of Jeff’s approach.

C: What do we want from a teacher? And how much do we want them to be sharing their traumas with us. As someone who teaches, I think the demand that the teacher shares with us, their students, their vulnerabilities, their problems, is a very specific pedagogical method that I see a lot of problems with.

B: Ya, when people disclose too much about themselves, whether it’s psychoanalysts or teachers, I’m like, I don’t want to hear your stuff. I really want boundaries with my teachers. And I wanna have boundaries as a teacher, like the Gazing Ball. But if you tell me a story, I do want some drama, and there is no drama in his stories. That’s why it’s a bit boring to me.

D: He’s impenetrable.

B: I think we should have spoken more about his relationship to capitalism. Maybe if you grew up as a white man in the ’50s in America you were just surrounded by capitalist positivity. I do find it remarkable to see an example of a human being who managed to carry that through to this point. There’s someone who experiences commodities as positive and beautiful in their childhood, and somehow the illusion of this experience has not been broken into pieces.

C: Yeah, this is the question: Is he announcing a capitalist spirit through a self-help type of individualism? Or, in his ambition of promoting art as something that everyone can learn, as a set of techniques, is this a democratic socialism? Because in many ways the legacy of the romantic Bohemian artists of the 1830s are much closer to the capitalist spirit than the academic orthodoxies. This idea that either you have it in you or you don’t, but you certainly cannot learn it. That’s a brutal predicament because you never know if you have it until you’re dead.

A: For Koons, when someone buys a work, it means that they want to take care of it. It means they’re making a commitment to it, an emotional commitment.

C: Because his objects are supposed to provide transcendence. So why is he so adamant that it’s not about the money? It feels inflected by Protestantism. But maybe there is also an ’80s spiritualism here. Like when you are talking about the basketball work and the feeling of Nirvana. So you have quite different religious references in his work that all can be distilled into something divine.

D: He’s actually thinking that his things are gonna survive for a thousand years.

A: He sent something to the moon, right?

C: Yeah.

B: 400 BC sculptures of the future. No question.

D: It’s against death, that’s what it is.