double-loved

Richard Prince at Gagosian

May 10

–

June 25, 2022

Richard Prince’s use of quintessentially Ballardian tropes — the nurse, the war, actors, pornography, JFK, advertising, magazines and the car — is as much montage as it is fandom. His voracious appropriation is less about the obvious symbolical meaning of American postwar culture but of things used many times over: “Over-determination was part of his plan, and in a strange way, the same kind of psychological after-life was what he loved, sometimes double-loved, about her picture.” (“The Perfect Tense,” Richard Prince: Collected Writings, 2011). Ever the tear-sheet clerk at Time Life, ripping editorials out of former issues in a basement during night shifts that left him with the advertisement pages as refuse, this is Prince’s approach to all media, most famously reshot photographs. The urge can perhaps best be described as a fetish, to desire something used by another and to own it through an image. Psychoanalysis defines the dream as overdetermined, that is to say, its elements are defined at once by multiple different factors of the dreamer’s life. In order to make sense of their meaning these layers must be uncovered through interpretation.

Prince’s repetition is not interpretative in that it doesn’t serve to render a symbol, say of violence, more palpable. Rather, much like in dream, he derails meaning through the accumulation of reproductions.

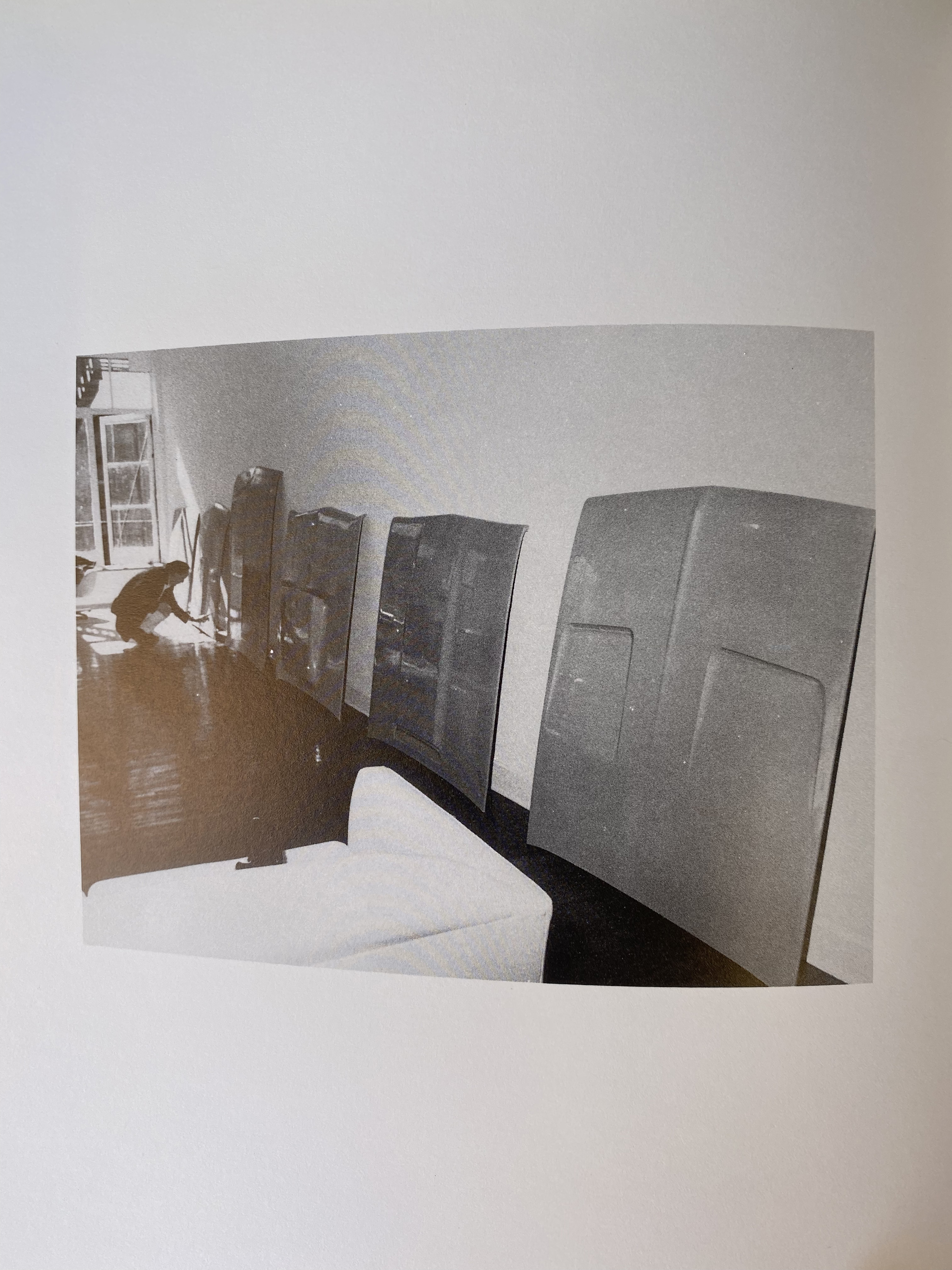

Produced over the span of 25 years, from 1988 through 2013, “Hoods” consist of wall-mounted, industrially fabricated car hoods that Prince initially commissioned body shops for and later worked on himself, employing the automotive body filler Bondo and paint. The surface of the works varies greatly, from smooth and velvety to glossy pitch-perfect to visibly overhauled and worn.

As per the press release of the show, hoods “relate to two postwar American trends: DIY car culture and avant-garde art in their exploration of abstraction and the readymade.” The importance of the show is indeed related to both, however with a crucial temporary disjuncture.

First, despite the fact that we keep driving them, hoods as synecdoche for cars as symbols for sex and speed in advertising has all but ended. Fuel prices and climate change aside, what was already the last vestige of eroding masculinity at the tail end of Prince’s production process — so smartly expressed by his gradual reintroduction of the painterly gesture — now finally is starting to have the quality of civilisatory debris. Ballard’s anatomy of triggers — the superimposition of the splayed-out naked female body on speeding vehicles — has given way to the static serenity of relics. Part of the appeal of “Hoods” in 2022 is owed to the faux ornamental of historic artifacts: What were these for? They are not pathetic though since there is no longing for reanimation. To the contrary, the dislocation of the hoods from cars as classic tropes of pop culture within a speculative post-technological landscape increases their abstraction to a brutal kind of beauty.

Second, “Hoods” evoked a no-shame attitude because it seemed such an impossibly formal and visually appealing show while effectively admitting to its own genealogical stupidity: car hoods. It is tired to bemoan the narrative dogma of contemporary art but suffice it to say that in an unlikely twist, these ten-year-old works encapsulated and responded to a growing fatigue with the literalized readymade as a vessel for allegedly critical, mostly textual meaning. These are hoods; some of them beautifully painted.

The reason this 2022 showcase of ten-year-old work is good should not be confused with an argument for objective formal quality or conceptual timelessness. Prince is alive and he chose his own work as material. Nothing needs to be restored in this perfectly timed setup. The humor resides within the shortness of time it takes to change an image, and Prince knows this.