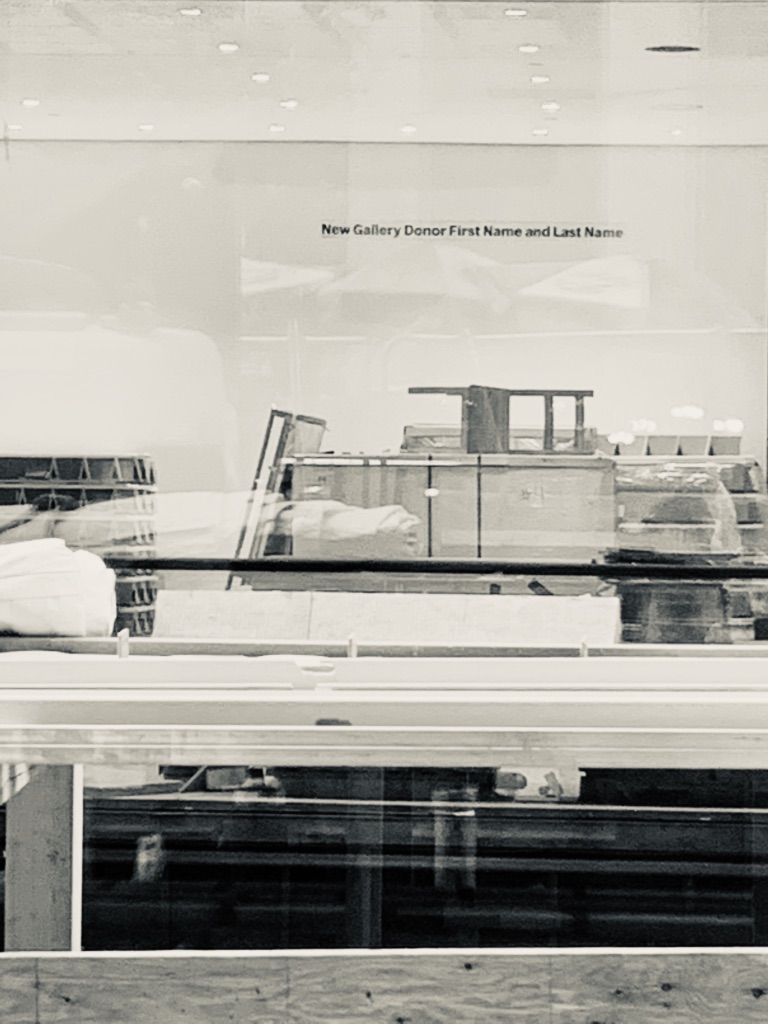

#newMoMA?

In June 2019, before the Museum of Modern Art closed to visitors for its much talked about expansion, the New York

Times art critic Roberta Smith asked, “Will there ever again be such a large gallery devoted entirely to Matisse’s most radical paintings of the 1910s? Or to the founding of Cubism, which at MoMA is 90 percent Picasso? How about Monet’s “Water Lilies,” a longtime constant?” The answer to all these is a resounding yes! While many were relieved that these canonical works had not been consigned to storage in an attempt to radically rewrite the history of modernism in an institution that is largely responsible for both drafting and crystallizing its textbook telling, others were left to wonder: What really makes this a

new MoMA?

The institution promises frequent rotations and makes some room for unfamiliar pairings

: Alma Thomas is

juxtaposed with Matisse and Faith Ringgold problematically pitched alongside Picasso in a gallery unapologetically titled, “Around

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” That these changes are additive and not structural is all too apparent when, for example, “colonialism” and “capitalism,” as conceptual terrains and lived conditions, are barely acknowledged — let alone foregrounded — in MoMA’s version of the long 20th century. Its desegregation of media in the galleries stands out as a significant achievement, relative to its own obsolete medium-specific organization, though the curatorial conceit of wanting to own and tell the whole story continues to get in the way of a profound reckoning with the institution’s deep-seated parochialism (of the center, no doubt). Inevitably then, MoMA is yet again left playing catch up after its plutocratic Board footed a staggering $450 million bill for increased space to reinvent the Museum, a feat arguably all too possible within the amplitude of its former real estate.