After the Sky

Melancholia at Metrograph

February 27, 2020

As the familiar strains of the Wagner prelude trumpeted over the end credits, the man to my left grasped the seats in front of him, lowered his head, and let out a long-stifled sigh. We had just watched the end of the world, or the version of it depicted in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia (2011). It was three days before the first reported case of COVID-19 in New York, and the smattering of us in the theater that night were all there with the same morbid purpose, a kind of mediated girding for the impending calamity.

During the beginning stages of the pandemic, there was a strong appetite for disaster films. Soderbergh’s Contagion (2011), with its dogged commitment to scientific realism, rose to the top of rentals as pandemic fiction par excellence — a film that was leveling with us, more attuned to our present than the fantastical premise of Melancholia. In a moment when the months ahead were shapeless and unknown, it provided a sobering but ultimately hopeful sanctuary — a kind of cinematic exposure therapy — where we could grieve the death and disruption that in life would be too painful, too ineffable. The more on screen we recognize in our own situation — the closer the film hews to reality — the stronger the catharsis.

Realism is, however, only a relational distinction, its tropes (i.e., grittiness, low lighting, simple dialogue) reactions to narrative convention rather than any direct engagement with reality. A realist disaster film in particular must contend with the decidedly un-narrative indifference of the entity at its center: A virus or a volcano or an asteroid does not act out of malice. It makes for an unsatisfying enemy when our narrative sensibilities look for heroes and villains. Cuomo speaks frequently in his press conferences about “love winning” against the virus, which implies that the virus personifies the opposite of love — that is, hate or evil. We can believe in an end because we believe that good does ultimately prevail.

In Contagion, the end (a vaccine) comes about only when a single scientist bypasses the bureaucratic testing process and inoculates herself at great risk. The primacy of individual action is a hallmark of American culture and its righteousness has been at the center of the debate around the coronavirus response. In the absence of a cohesive and well-communicated strategy from above, we are left to scrutinize our own multitude of choices from an endless spectrum of individual perspectives, to balance received wisdom with personal need and to adapt to their turbulent daily reconfigurations.

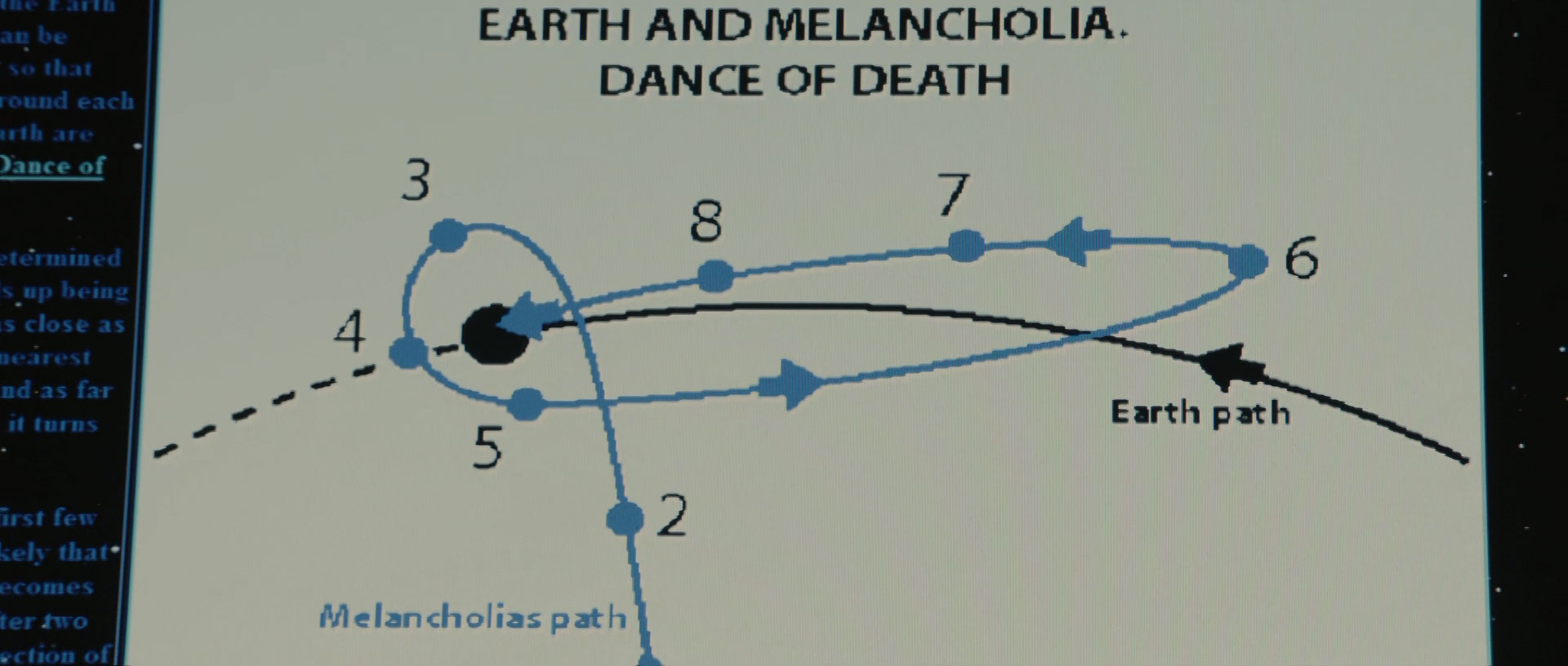

Melancholia’s apocalypse does away with these variables. There is no during inside of which to ponder. The apocalyptic event is flattened into a before and after, a monstrous, perfect totality — all at once and without distinction. It is alien, not of us, does not cause us to be suspicious or wary of each other. It does not divide the world up, or reinforce borders, rise and plateau, or dole out suffering unequally.

Is this a seductive and indulgent nihilism, particularly when we are surrounded by the failings of the global order, the incompetence of our leaders and the impossibility of a decisive conclusion? The sigh of the man to my left was not from despair but in relief — for a deeply felt optimism, an apocalypse on the best possible terms. One whose doom cannot be reduced to a function of evil. It is no surprise that the film ended up on the short list of movies that Bernie Sanders keeps on his iPad.