As a rule, ceilings do not exist

Encountering art fairs online

March – June 2020

Perhaps you looked at them too: the online viewing rooms that replaced this spring’s art fairs. Art Basel Hong Kong in March. Frieze New York in May. FAIR, an initiative by NADA, later that month and into June (notable for its admirable profit-sharing model). And then, Art Basel proper in June. Instead of booths or exhibition spaces, there are grids of thumbnails of available works, generally organized by gallery. Each work can be clicked on to obtain more information and to view more closely, from different angles and distances. It’s not unlike shopping for clothes online.

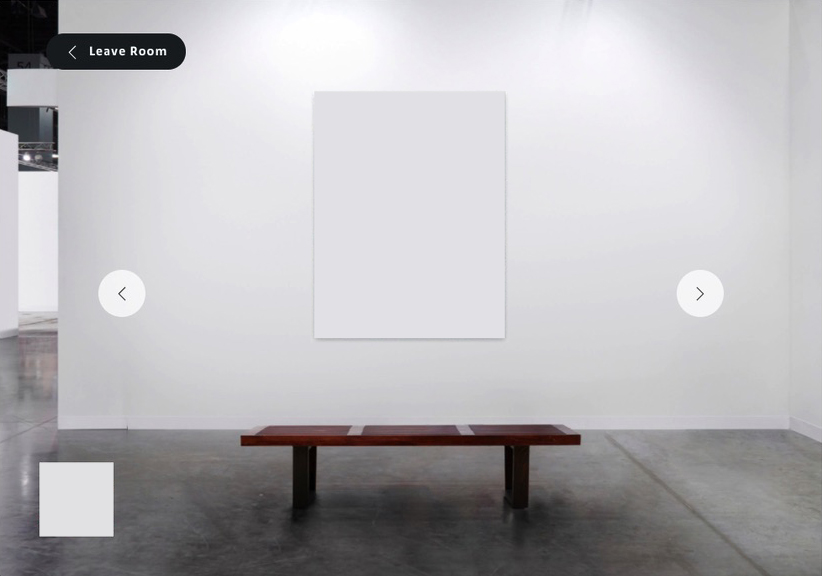

But let’s be clear, there is no room. In fact, only planes exist: the screen and the wall, since all of these digital platforms promote a feature to virtually view a single artwork against a wall. Entirely unlike a fair, works cannot be installed together, interacting in a three-dimensional space, and can only be seen together as hovering thumbnails. So there is either the white screen or the white wall. The difference is subtle.

The wall takes on hue and value, presumably to evoke some physicality, and may extend endlessly to the edge of the browser or conclude at some crisp margin. Art Basel Hong Kong contrived depth and perspective by allowing a glimpse beyond the wall to a vague environment. Flooring and furniture work similarly, establishing dysfunctional scale, and differentiating fair brands by the stain of their awkwardly positioned slat benches, the polish of their faux-concrete floors, or, in the case of the forthcoming Art Basel, industrial grey carpeting. As a rule, ceilings do not exist; no one wants to visualize the utilities. The online viewing room achieves an extraordinary monotony in its pursuit of illusionism, which is comically strict.

Most of these interfaces attempt realism by adding a drop shadow to each (image of the) work, which makes several assumptions: that the artwork is two-dimensional, rectilinear, maybe an inch or two deep, and meant to be hung on a wall. If the gallery didn’t anticipate these virtual conditions and uploaded an image that already included wall and shadow, shadows are duplicated and walls superimposed onto walls. Also possible — sculptures and installations acquire drop shadows, distorting them into photographic works.

The problem isn’t that people are willing to buy art from JPEGs, as some purists have exclaimed. Dealers have been selling works based on images or PDFs for at least a decade (and before that printouts and slides). It occupies the same reality as reviews being written about shows only visited on your browser, articulating an open secret the jet-setting cultural pessimists don’t dare to admit: (Digital) reproduction does afford engagement with art, albeit at a different pace and distance. Rather, the problem is the paltry capabilities and imagination of the online viewing room’s virtual illusionism, the technology exposing the extreme conservatism undergirding the art fair business. For now, the energy around the scale-view novelty seems as misplaced as the empty seating within — too close, too faraway, too oblique.